It was 1997 when Gattaca was released; a science fiction film about a future in which it would be possible to give birth to human beings with a precise genetic make-up, selected by their parents from a certain group of embryonic cells.

Well, that future is now.

The polygenic test

In fact, an investigation by Bloomberg reveals clinical trials of gene editing on human embryos; the aim of which is to lower the odds of the child having heart disease, diabetes or cancer in adulthood. This is the so-called “polygenic test”. Companies offering this “service” to couples wishing to have children according to their desires can be tracked down via the Genomic Prediction website. Rafal Smigrodzki, a North Carolina neurologist with a PhD in human genetics and one of the parents who went to one of these clinics, tells Bloomberg that parents have a duty to give a child the healthiest possible start in life. “Part of that duty is to make sure we prevent disease. That’s why we give them vaccines,” he said. “And polygenic testing is no different. It’s just another way to prevent disease.”

The mirage of the “healthy child”

However, it’s a way to prevent disease that implies results that are by no means obvious. As Bloomberg also reported, (from the New England Journal of Medicine July issue) thirteen scientists sounded the alarm regarding this: the risk is that customers, (i.e. parents) are being lured by the mirage of having a 100% “healthy child”. But, the scientists note, “scores” on the polygenic test “are only possibilities, not guarantees.”

The “perfect child”

But in addition to preventing disease, the growing number of parents are also turning to these clinics to “have a child made” with a certain physical appearance and strong intellectual gifts. Smigrodzki, the parent surveyed by Bloomberg, doesn’t hesitate an instant: “It’s right and proper that every child should be smart, that every child should be above average,” he says.

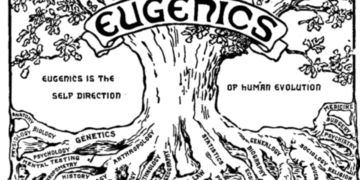

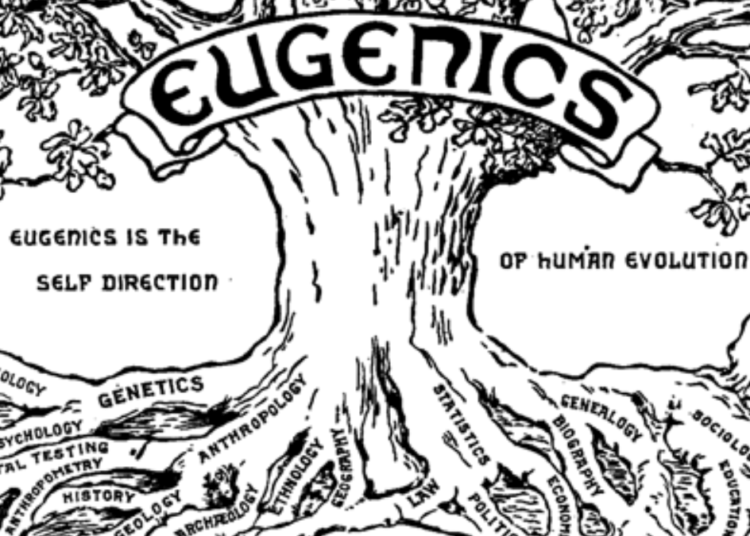

The risk of “liberal eugenics”

However, the prospect of intelligence-based selection raises understandable concerns. Steven Hyman, director of the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, calls it a more subtle eugenics than the eugenics of the late 19th/early 20th century–i.e. “a liberal eugenics”. For Hyman, it is therefore necessary to set ethical stakes from the outset, before the discriminatory principle of the perfect few takes hold.

Discussion about this post