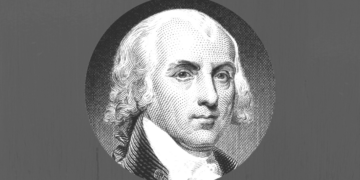

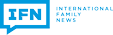

Madison and his work

“No man is more responsible for the U.S. Constitution,” wrote Notre Dame Professor Vincent Phillip Muñoz, “than James Madison. Leading delegate at the Philadelphia Convention, advocate and expositor as Publius [in The Federalist Papers], author and sponsor of the Bill of Rights, Madison rightfully earned his title ‘Father of the Constitution.’” A closer look at Madison’s role in the Convention was provided in a recent report by Brenda Hafera of The Heritage Foundation.

At 36 years old, Madison was one of the youngest representatives at the Constitutional Convention, an unassuming man who was only five feet four inches tall, was often dressed in black, and had a weak voice. Yet he was an indispensable delegate, matched in argument perhaps only by Pennsylvania’s James Wilson. It was Edmund Randolph who presented Madison’s Virginia Plan that gave structure to the new Constitution and framed the conversation for the remainder of the Convention. In his defense of individual liberty, Madison advocated for separation of powers, checks and balances, bicameralism, and federalism. When the American people (and some of the delegates from that same Convention) clamored for a Bill of Rights, James Madison took the lead in drafting it. Of utmost importance to Madison was freedom of conscience—America’s “first freedom.”

Glimpses into the workings of Madison’s own conscience appear in comments he made such as that to William Bradford: “A watchful eye must be kept on ourselves, lest while we are building ideal monuments of renown and bliss here, we neglect to have our names enrolled in the annals of Heaven.” Or such as that made to Edmund Randolph explaining that at one period in his life, Madison undertook the study of law “to provide a decent and independent subsistence” and “depend as little as possible on the labor of slaves”—a remarkable sentiment for one born into an affluent, slave-holding family.

His impeccable reputation for honor is evident in Jefferson’s observation that in the entire time Madison was under the tutelage of the acclaimed Scottish divine John Witherspoon, president of Princeton (as the institution came to be called), he never knew Madison “to do nor to say an improper thing.”

What Madison did do was single-mindedly gather the wisdom that would soon prove indispensable to the establishment of America. “For the great tasks of his life, such as the Constitutional Convention,” wrote historian Saul Padover, “Madison prepared himself with overwhelming and sometimes health-breaking thoroughness,” reading “the most important and authoritative works in the fields of politics, history, comparative institutions, jurisprudence, international law, and particularly accounts of ancient and modern confederacies. He bought as many books as opportunity permitted,” and “when Jefferson was American Minister to Paris, he served, among other things, as Madison’s book buyer.”

“No two men could have been closer,” continued Padover, and “history records no comparable friendship of similar duration and depth of esteem.” Of his friend Madison, Jefferson wrote in his Autobiography,

Mr. Madison… acquired a habit of self-possession which placed at ready command the rich resources of his luminous and discriminating mind, & of his extensive information, and rendered him the first of every assembly… of which he became a member. Never wandering from his subject into vain declamation, but pursuing it closely in language pure, classical, and copious, soothing always the feelings of his adversaries by civilities and softness of expression, he rose to the eminent station which he held in the great National [Constitutional] convention of 1787…. With these consummate powers were united a pure and spotless virtue which no calumny has ever attempted to sully. Of the powers and polish of his pen, and of the wisdom of his administration [as President] in the highest office of the nation, I need say nothing. They have spoken, and will forever speak for themselves.

So it could be said also of the Constitution to which Madison contributed so profoundly. Its immeasurable benefit to America is self-evident—even if others have added their own adulation. British Prime Minister William Gladstone called the document “the most wonderful work ever struck off at a given time by the brain and purpose of man.” And according to Professor Matthew Spalding, “The creation of the United States Constitution… was one of the greatest events in the history of human liberty. The result of the convention’s work has been the most enduring, successful, enviable, and imitated constitution man has ever known.”

Rewriting history, distorting reality

It is hardly surprising, then, that the campaign to malign America’s Founding and her Constitution would target its chief architect, James Madison. Referring to the “Soviet-like rewriting of history” to “undermine Americans’ love and respect for their country, their Constitution, and their civic way of life,” Arizona State University Professor Colleen Sheehan points to Hafera’s report as the “go-to” document that exposes the Marxist assault on “virtually every aspect of American life, including at landmark sites of our nation’s history” and especially at Madison’s Montpelier, where “woke revisionist history reaches a new and dismally shocking level of ideological manipulation and deceitful distortion.”

Introducing Hafera’s report, Heritage President Kevin Roberts notes that Montpelier’s exhibits and tours, like those at Jefferson’s Monticello, have relegated the achievements of its owner “to the background—at best, an indefensible oddity,” as “historical interpretation has descended into a contorted narrative poisoned by the inanity of modern political correctness. The fact that these distorted views are funded by so many radically left-wing foundations and activists at least proves the point: History matters.”

Chief among those radical groups is the notorious Southern Poverty Law Center, which has also targeted the International Organization for the Family as a hate group. According to Hafera,

James Madison’s legacy at Montpelier has been effectively erased, as there are no exhibits dedicated to his significant contributions. Montpelier can now be counted among the ranks of projects and actors that promote a distorted view of American history, suffused with critical race theory. There is a great deal of overlap between the curriculum developed by the Southern Poverty Law Center, a political interest group that is widely regarded as extremist and that maligns reputable organizations it disagrees with as “hate groups,” and the exhibits at Montpelier. Montpelier has solicited SPLC associates’ involvement on multiple occasions, and the results are dispiriting and insidious.

A video shown at the Montpelier Visitor Center, notes Hafera, portrays “Madison [as] a slaveowner and the Constitution as racist, stating that it applied only to white men like himself,” but fails to disclose that “the delegates at the Constitutional Convention deliberately rejected codifying the principle of property in men. While the Constitution does contain provisions that pertain to slavery, such as the Fugitive Slave Clause, that decision [to reject the principle of property in men] proved crucial as it ‘became the constitutional basis for the politics that in time led to slavery’s destruction.’”

While the Heritage report does not seek to minimize the moral repugnance of slavery in the Founding generation, it insists that a focus on slavery to the exclusion of everything else is to throw the baby out with the bathwater. “The problem today,” Roberts insists, “is that the predominant way we ‘do history’ in our classrooms, museums, and historic homes is a violation of the historian’s first objective—to let the evidence, not our personal biases or modern sensibilities, form the basis of our narrative.”

For while “the historical records of the enslaved… are important, good, and even rejuvenating, both for our history and for our contemporary civic life,” says Roberts, yet “emphasizing them… at the expense of the achievements of those very men whose ideas and actions made it possible to build, however imperfectly and slowly, a republic in which everyone was free, undermines not just the accuracy of our history, but also the belief in our shared principles as a pluralistic republic animated by our zealous commitment to self-governance.”

Imperfect men, enduring truths

In an afterword to Jon Meacham’s book In the Hands of the People, African-American Harvard law Professor Annette Gordon-Reed tells of her first visit to the Jefferson Memorial where she met a Somali immigrant who turned out to be an ardent admirer of Jefferson. “She offered,” says Gordon-Reed, “that Americans did not sufficiently appreciate the benefits of living in a society in which the government proclaimed no religious orthodoxy—indeed one in which a respected Founder had taken a position against such an orthodoxy so clearly and steadfastly.” Gordon-Reed was “more than a little taken aback.”

A young female African immigrant, now citizen of the United States and Thomas Jefferson enthusiast, was not at all who I expected to encounter when I decided to make my first foray to the Jefferson Memorial. Unlike many people I talk to about Jefferson, this young woman had read a good deal of what he had written. Her judgment was considered. Still, I raised the obvious and difficult questions: What about slavery? What about race? “Oh, I know all about that,” she said with the wave of a hand. Everyone has flaws. But in this case, as far as she was concerned, the flaws did not outweigh his contributions or the importance of his more admirable ideas. I pressed a bit harder on the point. But she was unfazed. Americans, she said firmly, fixate too much on the person and not the ideas. For her, Jefferson was about the ideas, the words that voiced truths that had staying power across the ages and geography.

The incident underscores the tragedy described by Hafera: “Rather than being remembered for their remarkable contributions, the Founders are being discredited, their legacies distorted or erased.” It is a dangerous irony that the freedom bequeathed by the Founders is being used—or rather, misused—to dishonor their legacy and the foundation they established to secure that very freedom. Mark Levin has written,

The counterrevolution to the American Revolution is in full force. And it can no longer be dismissed or ignored, for it is devouring our society and culture, swirling around our everyday lives, and ubiquitous in our politics, schools, media, and entertainment…. It threatens to destroy the greatest nation ever established, along with your freedom, family, and security…. The counterrevolution or movement of which I speak is Marxism.

Nothing could be more anti-American and anti-Madison than Marxism, the brainchild of Karl Marx whose 1848 Communist Manifesto declared religion to be “the opiate of the masses” and literally proposed doing away with the family as an archaic bourgeois institution.

Preserving the priceless

The Marxist distortion at Madison’s Montpelier must be corrected, but that is just the beginning. Levin urges, “We must rise to the challenge, as did our Founding Fathers, when they confronted the most powerful force on earth, the British Empire, and defeated it.” President Ronald Reagan’s caveat has never been more urgent.

Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction. We didn’t pass it to our children in the bloodstream. It must be fought for, protected, and handed on for them to do the same, or one day we will spend our sunset years telling our children and children’s children what it was once like in the United States where men were free.

On August 27, 1975, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie was secretly assassinated in a Marxist coup. Years earlier this esteemed leader, who President Eisenhower had once greeted at the White House as “a defender of freedom and supporter of progress,” left this sober warning:

It has been the inaction of those who could have acted; the indifference of those who should have known better; the silence of the voice of justice when it mattered most; that has made it possible for evil to triumph.

It is time to speak, to act, and to protect the liberty for which Madison and the other Founders, imperfect though they were, valiantly paid the price. They were “animated by a sense of obligation, and of mission,” wrote Henry Steele Commager, not only to their own generation but also “to posterity.” It is now up to us to preserve that priceless legacy for our posterity.

Discussion about this post