Larry Flynt died yesterday. We should pray for his soul.

I take seriously the notion that it is not well to speak ill of the dead generally, and I feel acutely the demand to be particularly circumspect when it comes to addressing this particular individual’s impact on society.

Nonetheless, I’d be lying if I said I didn’t feel a certain amount of impatience and frustration with the headlines I saw reporting the matter last evening. CNN, the Associated Press, and others all found room for definite, if qualified, praise of Flynt’s “legacy.” In CNN’s words, Flynt was an “outspoken First Amendment activist.” Other treatments had almost the tone of a panegyric; for instance, this, from CBS News:

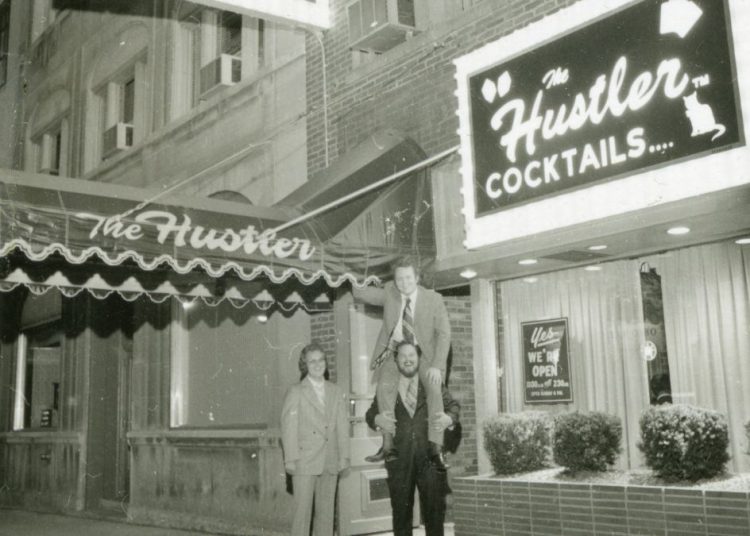

From his beginnings as an Ohio strip club owner to his reign as founder of one of the most explicit adult-oriented magazines, Flynt constantly challenged the establishment and became a target for the religious right and feminist groups.

Flynt scored a surprising U.S. Supreme Court victory over the Reverend Jerry Falwell, who had sued him for libel after a 1983 Hustler alcohol ad suggested Falwell had lost his virginity to his mother in an outhouse.

I suppose it’s at least somewhat gratifying that the author found a way to figure “feminist groups” into the equation, alongside the “religious right” and Reverend Falwell—partially (though only partially) attenuating the latter’s functioning as typical “boogey men” in the piece.

It is unavoidable, however, that there is more that can, and must, be said about Flynt. He is a figure in many ways representative of our epoch. I want to go further, though, than simply counter-balancing the popular press’s milquetoast approach by pointing out the obvious criticisms (which, to their credit, even many of the mainstream media pieces acknowledge). After all, it is for God, not me, to judge Flynt. Instead, I’d like to comment on how Flynt, in his person, represents a sort of a judgment upon our times, and indicate what lessons that might bear for us.

Firstly, then, it is undeniable that Flynt was a perpetrator of monstrous moral evils. Beyond his very public sins as a pornographer, he has also been accused of sexually abusing his own daughter, though he denied the charge. If true, of course, no excuse can be made for this: about that we must be very clear. There are elements in Flynt’s background that indicate partial explanations, however—which, again, do not amount in any way to excuses—for what led to him becoming the morally corrupt man he did become. His own childhood had no lack of trouble. His father was absent for much of his early youth. When he was nine years old, his younger sister (age four) died of leukemia. The death precipitated his parents’ divorce, and he was separated from his brother to be raised in separate homes, Larry being raised primarily by his mother. He bounced back and forth between hers and his father’s home, at times seemingly running away from one or the other. According to his own account, one instance of his running away from home was triggered by his having been picked up on the roadside (at the age of fifteen) by a stranger who proceeded to molest him at gunpoint. There are also some indications of an abusive relationship with his mother’s boyfriend. Yet, Flynt seems to have been a psychologically unstable individual from early life, and it’s difficult to know how much credence can be given to his own reminiscences. He may have stretched the truth for his own purposes. It is undeniable from the facts as observed from outside, however, that he was raised in an unstable and sometimes turbulent situation, and that his is another case of what too often happens: a victim of predation going on to act out as a predator. Even if the allegations of his daughter are false, Flynt’s career was built on preying upon the vulnerable. The upshot of all this is to remind us of a truth we too often allow to become cliché or trite: that, in Wordsworth’s expression, “The child is the father of the man.” We hear often that “charity begins in the home.” What is true of a virtuous nature is also true of a vicious nature. Laws and censorship can only do so much. If we really are determined to break cycles of abuse and depredation, we need to strike at the root. This is a lesson we must take to heart, and never forget, and a project in which we all must play our part.

Secondly, and relatedly, we must admit that as much as Flynt was an agent of the moral demise of our society, he was also a product of the same. As with the mass media about which so many of us complain, this is another case in which it seems really that we get what we deserve. There’s a certain cold logic of the law of supply and demand to the phenomenon that was Flynt’s pernicious publishing career. He’d never have become the tycoon he did if there hadn’t been those willing to buy his swill. In short, Flynt’s success was, truly and in multiple senses, “deserved” (as one can “deserve” what is discreditable as well as that which is creditable). I don’t mean primarily that Flynt “earned” his “success,” though of course he did: by preying upon the vulnerable, the sad, the lonely, the destitute and desperate. Rather, I mean in many ways our culture “deserved” the scourge of Flynt’s “success.” The groundwork for what he accomplished was laid by others. He stood on the shoulders of giants, as the saying goes; and these giants, as they are in almost every fairy tale, were themselves moral monsters. The sexual revolution, capricious divorce, the horror of abortion, the privileging of the animal part of the human person with its desires and urges, the moral relativism reducing all ethics to a consideration of whether someone is “hurting” anyone else, the commodification of sex and translation of sexualization into “empowerment”… all this and more formed the list of ingredients that constituted the recipe of Flynt’s success. He opportunistically exploited these potentials—but he didn’t create them. In many ways, they are all simply part of fallen mankind’s sinful nature. But the twentieth century also saw the actualization and expansion of these things in the decades and years before Flynt ever came on the scene. One is tempted to suspect that, had he never printed a single magazine, some other one like him would have arisen in his place: the thing seems almost inevitable. He was, indeed, a moral scourge, but the stripes our society bore because of him were in many ways earned.

Finally, Flynt’s story functions as a cautionary tale for us. We cannot forget, notwithstanding what’s been said above, that there was after all a “moral majority” that opposed Flynt, a part of the culture that was outraged by his provender and sought to quash it. But it doesn’t seem to have been a successful opposition. At least, the sequel certainly seems to suggest otherwise. Pornography in the online era has ballooned into a multi-billion dollar industry and a force propelling human, especially child, trafficking; and sexual mores have slid further and further away from the traditional morality in opposition to which Flynt served as a figurehead. Pornography is more ubiquitous and more graphic than ever before, and it ensnares every younger minds. Meanwhile, we’re seeing a new industry of what might be called “enacted pornography,” with the advent of life-like robotic sex dolls that turn what was once a passive experience of fantasy into an engaged reality wherein men can act out their most perverse (and sometimes predatory) imaginings, all (supposedly) without “hurting anyone.” The question is, why did we fail in this way?

As I noted above, there seems a certain ineluctable and inevitable force at work here. If one will pardon my punning, it seems as much a foregone conclusion as that my parents’ generation found Flynt, that my generation should go on to find Tinder. It’s beyond the scope of what I aim to do here to analyze every cause for why this is so, so I will focus on one facet of the issue. It relates to some of what has been said about, about vice as well as virtue beginning in the home, and about Flynt being as much a product of his age as he was a propulsive force. The fact of the matter is that there can be no dealing with the fruits of the sexual revolution piecemeal. The whole tree bearing that fruit must be chopped down at the root, and the stump burned. What we need is a thoroughgoing and complete ethics of sex, life, marriage, and family, or else all we are doing is clearing rotten fruit from the ground, fruit that will continue to fall from the branches overhead. Most of political and public opposition to Flynt was too narrow in its focus. As with every social phenomenon, the proliferation of pornography has its underlying causes, and we cannot simply deal with the symptoms: we must treat the disease. To borrow another metaphor, we cannot be content to sandbag at the levee if the dam is broken upstream: we must find our way upstream and stem the flood at its source.

This is, of course, easier said than done. But the logic is unavoidable. If we want to rid our culture of the scourges of exploitative pornography and sexual casualness, we need to recover and promote a positive and integral sexual ethics. We need to recover the primordial and primary moral truths written on the heart of the human person: that sex is meant for marriage, that family is its fulfilment, that man and woman are complementary in nature, that true love entails a complete and total gift of self, that children are the natural fruit of two persons’ intimate union, and that this life is sacred. We begin simply by sharing these truths. That the world may not want to hear this message will hardly come as a surprise, considering how willing the world has been to instead attune to the message of men like Flynt. Nevertheless, we can never tire or be timid in sharing the truth about sex, life, marriage and family. This may not be the news that our world wants to hear, or even deserves: but it is beyond doubt the good news that our world needs.

Discussion about this post