The image that heads the piece from The Guardian is far from sinister. There’s a touch of whimsy and even of joy to it. It might even remind some readers vaguely of the charming Pixar film Up, seeing apparent wonder radiating from the face of the old man as his greets his novel “companion.” That “companion” is a robot called Pepper, and it’s part of a new scheme to combat loneliness and promote better mental health outcomes for residents in UK care homes. One would dare say that the image of the old man and the robot seems initially heart-warming, and puts a smile on the viewer’s face. But that smile will inevitably falter as one begins thinking of all the image portends, and begins to ask the question that those conducting this study seem to have moved beyond entirely: How on earth did we get to this point?

The article mentions that a similar scheme to the one in the UK is being run with the same robots in Japan, as part of the same study. It is precisely with the mention of Japan that misgivings must arise for the wary reader, and that this story will begin to seem like anything but ‘good news’.

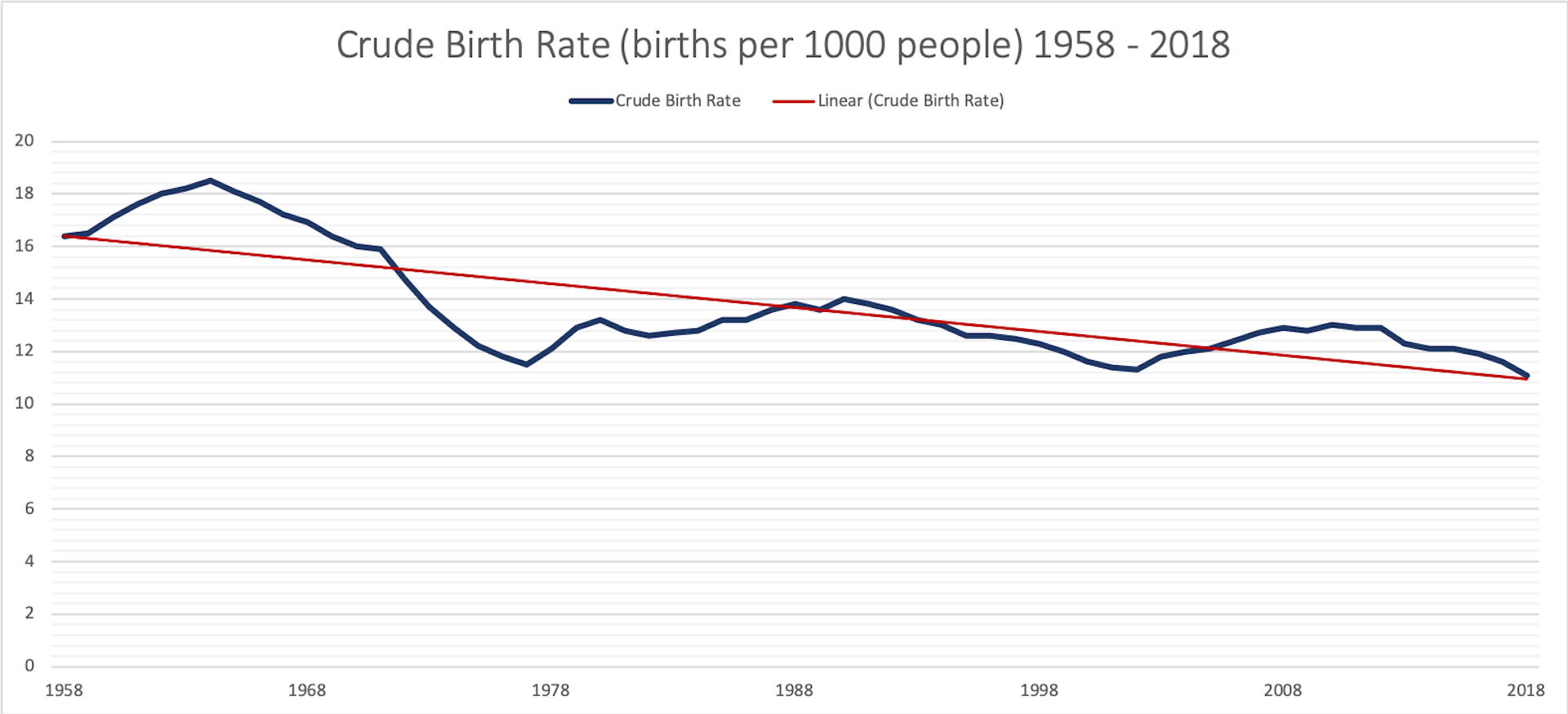

Japan, in recent years, has been a subject of increasing concern for demographers and economists, who have sounded the alarm about that country’s remarkably aging population and declining birth rate. A 2017 headline from Business Insider captures the situation in stark terms: “‘This is death to the family’: Japan’s fertility crisis is creating economic and social woes never seen before.” Both NPR and CNN have also reported on Japan’s fertility crisis, the latter noting, in December 2019, that Japan’s birthrate in that year had fallen to its lowest level since records began being reliably tracked at the end of the 19th century.

Similar concerns have begun being raised regarding the population of the United Kingdom. In April 2019, an article at The Conversation called the “dramatic” decline in UK live births “a national crisis.”

The article also spoke of the UK as “an ageing nation,” and highlighted some of the problems this generates, such as the strain on the NHS (National Health Service); but it also—notably—gave voice to the impact this has on the issue of proving care for the elderly:

There are 26.6m people in the UK aged between 40 and 79 – these are the people who, in the next 20 years, will be needing care or approaching that point. In contrast, there are fewer than 14m young people under the age of 19 – the people who in the next 20 years will be providing that care.

In light of all of this, the idea of robots accompanying the elderly and providing a simulacrum of socialization seems not so much a quirky and ingenious development of technology in a digital world, but rather a warning signal shouted from the crow’s nest that a nation is headed toward demographic shipwreck. This is to say nothing of the dehumanization and sadness inherent in the idea of an elderly person who, with no family or friends that will visit and whose nurses and caregivers are over-worked and encumbered with too many other charges, is made to satisfy their need for affection with the poor replacement of a humanoid machine. Even puppies or kittens filling this void would be a depressing commentary on a sad state of affairs… but robots? The idea is chilling.

The value of honoring previous generations is as well instilled in Japanese traditional culture as it is in the culture of former Christendom, where the commandment to “honor thy father and mother” from Torah stands alongside the New Testament admonition to visit the infirm and the sick (cf. Matthew 25:36 and James 1:27). Yet as demography has declined and cultural and economic philosophies have shifted, both of these age-old values have also deteriorated. First, the care of aged parents has increasingly been “outsourced” from the home to third-party caregivers (in a sort of recapitulation of the practice of paying a fee [qorban] rather than materially honoring one’s parents for which Jesus condemned the Pharisees in Mark 7:9-13). Now, in these latter days, even the duty of visiting the elderly and infirm has been found to have a technological workaround: robots will take care of this, just as they do other onerous or undesirable tasks like vacuuming our living room.

It’s a commonplace of science fiction to imagine an apocalypse in which robots play a part, usually by rising up in violence and making war on their human creators. But now, in science fact, we see hints of a different apocalyptic scenario involving robots and the death of humanity that is both more realistic and plausible, though by no means less frightening: robots caring for an aging remnant of a humanity that has turned its back on the values and family and life, and as a result dies the slow death of demographic decline. Elderly parents should have children, or at least a younger generation, to care for them; and for that, society needs healthier families, higher birth rates, and a more robust social, economic, and political order that values life at every stage. The efforts of such capable scientists as the ones conducting this study in Japan and the UK could probably be of better service to humanity in trying to helping achieve that end, rather than merely finding ways to soften time’s rebuke that inevitably comes when such things are ignored.

Discussion about this post