Last updated on June 14th, 2021 at 07:45 am

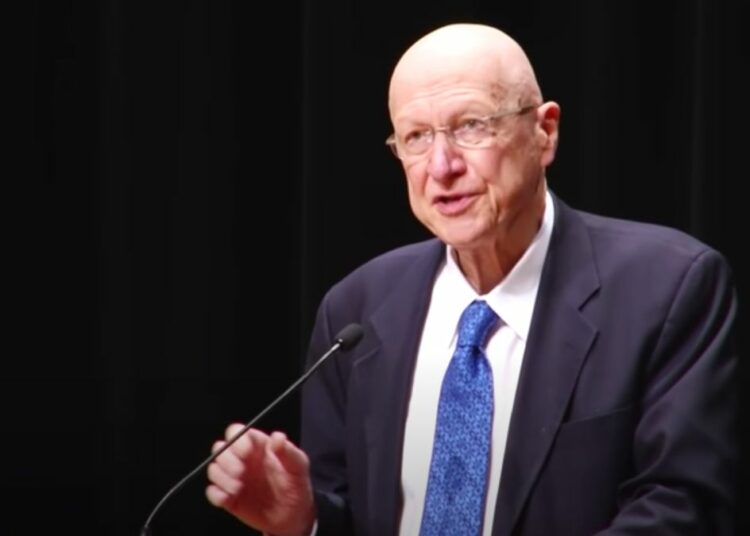

Dr. Peter Kreeft is one of the greatest Christian authors, philosophers, theologians, and apologists of the past fifty years. Professor at Boston College for over fifty years, he has written over ninety books and given thousands of lectures across the country at universities and churches. Some of the topics he has written about include the culture war (How to Win the Culture War, Ecumenical Jihad, How to Destroy Western Civilization), theology (How to Be Holy, Prayer for Beginners, Catholic Christianity), heaven (Everything You Wanted to Know about Heaven), St. Thomas Aquinas (Summa of the Summa, Practical Theology), Socrates (Philosophy 101 by Socrates, Socrates Meets Jesus), apologetics (Handbook of Christian Apologetics) and surfing (yes, surfing; I Surf, Therefore I am, If Einstein had been a Surfer).

During his years of teaching and lecturing, Dr. Kreeft has received numerous questions from his audiences. In the gem of a book Ask Peter Kreeft, he has compiled 100 of the most interesting questions he has ever been asked and the answers he gave. By reading this book, one will encounter Dr. Kreeft’s sharp mind, cogent analysis, and trademark humor and wish that the book would have gone on for another 100 questions. A look at some the questions and his answers will bear this out.

In answer to the question, “Why are philosophers weird?”, Kreeft responds: “My answer is simple: About 90 percent of all people who have ever lived have had children. About 10 percent of famous philosophers have.” (9) Why is having children such an important factor? Kreeft writes: “The world’s most effective teachers of morality are having children. Nothing makes your love more unselfish and wholehearted more quickly or more radically than having kids.” (9) Significantly, having kids also makes parents more religious. Kreeft states: “Parenting also makes the biggest difference in religion. Kids leave religion; parents return…The most common reason for returning is the kids. Like parachute jumpers, soldiers in foxholes, and big wave surfers, parents know they need God. And for similar reasons.” (10) Kreeft then makes a point that most of us have never noticed: that whether one has kids or not is the often the fault line in politics. “Whenever there is a public vote for any issue that has a moral component, the clearest, most predictable difference is not between Republicans and Democrats, or between conservatives and liberals, or between rich and poor. It’s between those who have kids and those who don’t.” (10)

In answer to the question, “Who was the first Christian philosopher?”, Kreeft has no hesitation. “Christ. He loved His Father and what His Father is, and one of the things His Father is, is wisdom, and philosophy is the love of wisdom; therefore, Christ loved wisdom and therefore was a philosopher.” (11) Kreeft then adds that if one wants to consider only human philosophers, the first and greatest one was Mary: “Her fiat to God contains all of human wisdom in one word.” (11)

When asked “What can we do for the cause of reunion of all the churches?”, Kreeft responds that the answer is sanctity. He writes: “It was sin and selfishness that divided us, so it will be holiness and love that reunites us…We know that His will is unity, so our disunity must have come from substituting ‘my will be done’ for ‘Thy will be done.’…Put a Mother Theresa in every denomination and denominationalism will eventually end.” (69)

In response to “I think Muslims are our enemies. What do you think?”, Kreeft hits us with hard truths. First, he notes that while Muslim terrorists are an abomination, the internal enemy is much worse: “The enemy within is far more dangerous and destructive to us than the enemy without. Terrorists are horribly wicked, hate-filled people. But they can kill only our bodies; traitors and heretics can kill our souls. So can priests who molest children. If terrorists deserve electric chairs, bad priests deserve millstones.” (72) Second, Kreeft reminds us that Muslims are our natural allies in the culture wars: “You would be hard-pressed to find a single Muslim in the world who’s pro-abortion. Or anti-family. Or pro-sexual revolution.” (72). Indeed, Kreeft notes that at the 1994 United Nations Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, it was the Muslim nations working with the Vatican that defeated the push by the United States and western Europe to make abortion an international right. At this conference, Kreeft writes, “Pope St. John Paul II fought and won a greater battle working with the Muslims than the Christians won against them in the Battle of Lepanto half a millennium earlier.” (73) Kreeft then gives us a poignant–and tragic–reminder about why Catholics are not winning the culture war: “George Weigel, the pope’s official biographer, said that the Catholic Church could win the culture war and get her social morality legalized by simply replacing every ‘Catholic’ politician in Washington with a Muslim or a Mormon.” (73) Indeed, it has been allegedly “Catholic” officials in Washington who have done some of the greatest damage to our Judeo-Christian culture–from President Joe Biden and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to Supreme Court Anthony Kennedy, who while on the bench led the charge to legalize sodomy and gay marriage and to keep abortion legal. Third, Kreeft says that Muslims can actually be our mentors in regard to revitalizing the Catholic Church because they practice what they preach:

“You’ll find wicked Muslims, just as you will find wicked Christians. But Christians—at least Catholics—have almost the same rate of murder, rape, abortion, divorce, adultery, fornication, sodomy, transgenderism, and just about every other possible perversion, as unbelievers do throughout most of Western civilization. We are no longer a distinctive people, as we were in the days of the early Church. Muslims, Evangelicals, Pentecostals, and Orthodox Jews are more distinctive in their lifestyle than we are. That’s the main reason we’re losing six times more people than we’re gaining every year, while those countercultural groups are all gaining.” (73)

When asked “Why not trial marriages—living together? Everybody does it today, even Catholics. It should cut down on divorce,” Kreeft first notes that people who live together before marriage are five times more likely to divorce that those who do not. Then he goes to the heart of the matter: “Why aren’t women insulted by being compared to cars? Why do women let themselves be used and abused by men in the hookup culture? It makes every college a selfish sex addict’s dream: it turns an educational institution into a free whorehouse.” (111)

When asked “Why the Catholic Church is obsessed with sex?”, Kreeft gives three answers. First, he notes that “The Church isn’t obsessed with sex; the secular culture is.” The culture is like an alcoholic husband asking his wife why she is so obsessed with his drinking. Second, he argues that “Church is right to be ‘obsessed’ with this obsession because the sexual revolution is ruining Western culture, ruining families, ruining souls, and ruining personal happiness, peace, and joy.” (125) Kreeft reminds us that the Church is truly only obsessed with one thing: God. And the sexual revolution is a complete turning away from Him. Third, and related to the second answer, the Church is “obsessed” about sex because sex is holy. Kreeft writes:

“’Sex is holy because it is part of the image of God, according to the Bible (read Genesis 1:27). Sex is holy because it is the way God designed to perform the greatest miracle in this world: the creation of the only thing in the universe that is intrinsically valuable, that is to be loved for its own sake, as an end and not as a means, that has infinite value and that is destined to possess eternal life, supernatural life, to participate in the very life of the Trinity.” (127)

“Why is the Catholic Church the only church that forbids birth control?” Because it denies the total giving of self to your spouse. Kreeft writes:

“What sex says with its body is total self-giving, but what contraceptive sex says with its mind and will is the opposite; I withhold this miraculous power of myself. I give you only the appearance, not the reality. I lie with my body. I hold back my most miraculous and precious power. I’m prudent and rational and controlled and scientific and mechanical and pragmatic and utilitarian. I’m not wild and crazy and romantic and risky and dramatic. I don’t want the lion; I want the kitten. I’m not a poet and a mystic, I’m a tame little pet.” (134)

“Why do people want to change their gender?” Kreeft pulls no punches: “Because the Devil hates them and hates their happiness, so he confuses them by making them hate something good, something God designed and made, something natural: their bodies. The Devil hates everything natural, because God created it. So the Devil always loves to pervert natural things.” (139) Importantly, Kreeft notes that we are to have compassion towards people wanting to change to their gender because “We cannot help them if we do not listen to them and understand them.” (140) Importantly, we need to “help them find peace and unity in their identity. And the way to do that is not to attack their bodies, as if they were mistakes, as if their sex organs were enemies that had to be killed, but to treat their souls, their minds and feelings, by psychiatry.” (140)

When asked “How can we be both just and merciful, both tough and tender, especially with our children?,” Kreeft tells us to look to Christ. “Christ is the answer to how to raise good kids. The more He lives in us, the better we are at everything important, including parenting.” (175) Then he adds that repentance and perseverance are also necessary: “But, of course, you will make a million mistakes. Repent. And never, never, never, never give up.” (176)

In response to “Why is there a war between science and religion? How did it begin?”, Kreeft denies that there is a war:

“There is no such war. It is a myth. Proof of that is the fact that not a single doctrine of religion—of the Christian religion, anyway—has ever been disproved by a single discovery of any science at any time in the history of the world. If you deny this, tell me: Which doctrine, which orthodox understanding of which doctrine, has been disproved by which discovery of which science or which scientist, when and where? Nobody has ever been able to answer that question.” (215)

And this is the case because God made the universe, the mind and true religion to always correspond with one another.

When asked “Which technological invention do you think is most dangerous, he unhesitatingly declares “the Pill.” Why? “The contraceptive made the sexual revolution possible, and that changed pregnancy into a disease and children into accidents. That is the most revolutionary revolution since Christianity because it is in fact undermining and eventually destroying the one institution that is absolutely necessary for human morality and happiness—namely, the family—and sending us straight to Brave New World.” (243)

“What is the most important thing we can for our culture? What’s the main thing missing?” Kreeft provides the answer he has to so many of the questions asked of him: Jesus. “Our culture is Christophobic. Let Christ come into your heart and your life, and He will do the rest. He will seep into your culture through a million pores.” (250)

To “Do you still surf?”, the octogenarian responds: “Does the pope still pray? Do fish still swim? There is no such thing as an ex-surfer.” (271) He also notes that since he lives in Massachusetts on the east coast, surfing has not always been easy. “I’ve been asked whether there are any waves in Massachusetts. I assure you, there are. I actually saw one; I think it was in 1978.” (271)

In response to “How important are pets?”, Kreeft responds: “More important than we think. For many of us, they are the best early-childhood training in life’s most important lessons, love and responsibility. They’re easy to love, and we need the easy lessons first.” (300) Indeed, these are the lessons that will help take us along the road to sanctity.

In Ask Peter Kreeft: The 100 Most Interesting Questions He’s Ever Been Asked, Peter Kreeft has crafted yet another masterpiece among his over 90 books. With profound questions mixed with lighter ones, the book displays Kreeft’s trademark love of the truth, insightfulness, clarity of thought, and wit. Upon finishing the book, one wishes that Kreeft could have answered 100 more questions. I guess we will have to wait; but seeing on his website that he has more books in the works (Kreeft turned 84 in March!), we just may get our wish.

Discussion about this post