Last updated on April 5th, 2021 at 11:43 am

The origin and history of April Fools’ Day is, appropriately enough, a rather debatable and elusive subject of inquiry. Theories about it range from its explanation having to do with the change from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar; to its being linked to the ancient Hellenic feast of Hilaria held around the vernal equinox; to it having arisen simply from climate cycles—the idea being that this time of year, the weather makes fools of us, as maybe we begin planting our gardens only to be shocked by a sudden unexpected frost. (I can sympathize with this latter theory. Having had a pleasant evening last night out on my porch in just a tee shirt, I see that the forecast tonight shows the temperature is expected to dip below freezing.)

Whatever the origins of this annual celebration, I think we can be more definite when remarking upon its current and continual cultural appeal. And this year, in particular—with April Fools’ Day coinciding with the celebration of Maundy Thursday in the Western Church—provides an opportunity for even deeper reflection on the phenomenon, inviting us to look at its spiritual aspects.

No, this isn’t an April Fools’ joke: I really do mean to suggest that this secular celebration relates to religious sensibilities in certain striking and profound ways. I understand if you have your doubts, but I’d ask that you bear with me—or, shall we say, at least to suffer this fool gladly, keeping an open mind.

No small amount of ink has been spilled on the perennial appeal of the Fool in culture, from the paradoxically perceptive Puckish fools in the plays of Shakespeare to the living witness of the Holy Fool for Christ, of which St. Francis of Assisi is the paradigmatic example (at least in the Western tradition). Besides the role of the archetypal Fool character, though, there is also a significant strain to be observed throughout history having to do with the characteristic of foolishness itself. For instance, there is the name “Folly” that is given to architectural adornments on a landscape that serve no practical purpose but function as mere extravagances and decoration. There are also the various Medieval traditions having to do with foolishness, like the “Feast of Fools,” the “Feast of the Boy-Bishop,” or the “Feast of Asses.” For those unfamiliar, these were festivals, usually held around the Christmas season (a significant point we will return to later), which were marked by social reversals and upheavals. The sumptuary laws and other social norms governing how people could dress and behave according to their station in life were, for the time of the festival, put aside, and the poor peasants would dress up as nobles or ecclesiastics, while the high-born would participate in their own ways by abandoning somewhat their normal dignity and propriety. The occasions were even overseen sometimes by a figure whose role was called Precentor Stultorum—literally, “Leader of the Foolish,” but often translated as “Lord of Misrule.”

Now, April Fools’ Day does seem to share at least this much in common with these traditions: that it likely arises from a natural impulse for wanting a sort of occasional “release valve” for the incumbent strains of a highly stratified society. The lowly station of the Medieval poor, for example, if left to simmer in built up resentment and frustration, might spill out in violent ways, like Wat Tyler’s revolt or other peasant uprisings. It seems natural that society would attempt (perhaps even unconsciously) to stave off such outcomes by arranging occasions wherein people could “let loose,” exercising their frustrations in relatively more benign ways, if perhaps ways that were a bit irreverent and embarrassing.

I don’t intend to suggest that April Fools’ Day in its origins had similar sentiments of popular piety behind it as did these other feasts—as I said at the outset, the history here is very difficult to pin down. But I do think that we can appreciate April Fools’ Day through the lens of the Advent and Christmastide festivals of foolishness regardless of the original intents and purposes; and I do think the seasonality of these occasions is at least suggestive, i.e. that there should arise around the time of Easter a celebration similar to those foolish affairs that had arisen in connection with Christmas.

So, what are the religious and pious underpinnings of those Christmastide feasts? And why would “borrowing” those sentiments for an understanding of April Fools’ Day, around Eastertime, be spiritually beneficial?

At the root of the “Feast of Fools” and other like celebrations is the phrase from Mary’s Magnificat recorded in the Gospel of Luke: “Depósuit poténtes de sede, et exaltávit húmiles”—“He hath put down the mighty from their thrones, and has raised up the lowly” (Luke 1:52). Indeed, these feasts were sometimes alternately called the Festum Deposuit.

Now, it is obvious why celebrations associated with the “deposuit” might crop up in the Advent and Christmas seasons: Mary’s prayer is recounted in the Infancy narrative of Luke’s Gospel. Connecting this notion with Holy Week and Easter, on the other hand, has to do with the meaning of the text, rather than its place in the narrative. Mary’s song in Luke 1:46–55 is laden with allusions drawn from the Jewish Scriptures and popular expectations of the Messiah. It would be burdensome and boring to simply cite a panoply of verses; suffice it to say that anyone familiar with Isaiah, Ezekiel, Hosea, or the Psalms—to name just a few books—will recognize echoes in Mary’s song of the Messianic hopes scattered throughout these texts: God scattering his enemies, uplifting the poor and lowly, confounding the kings of the earth, making fools of the wise…

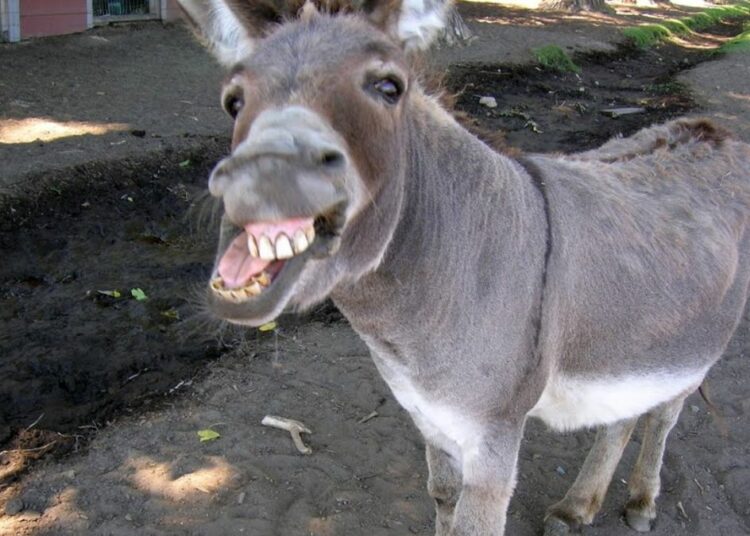

The same sort of paradoxical reversals surrounding the Incarnation of Christ—His being born in lowly estate, of a virgin, and so forth—are also attendant in the events at the completion of His earthly work: He enters Jerusalem riding a humble beast of burden rather than a mighty war horse; the crowds shout for the release of Barabbas rather than the true Son of the Father; He is finally given the crown the crowds cried for, but it is a mockery made of thorns. Of course, the biggest reversal of all is the end of the story: his followers come looking at the only place they’d expect to find Him after what they’d seen, and they find the most unexpected thing of all: an empty tomb. He’d told them to expect this; but they were fooled.

In respect both the Infancy narrative, and the Passion narrative, we find the same paradoxical subversion of expectations. Christ as the expected Messiah does fit the mold, but not in ways anyone expected. And therefore, the Messiah’s reign as it really came to pass continued to this day to be seen as a kind of misrule in the eyes of the world. A king might be expected; but his crown wouldn’t be expected to be of thorns, nor his kingdom “not of this world.” A judge might be expected, to raise up the lowly and give justice to the poor; but not such a one as would consort with and call prostitutes and tax collectors to conversion! A prophet might be expected, who would lead his people as a shepherd tends his flock; but what a shepherd!—profligately seeking after the lost sheep, and leaving the ninety-nine in search of the wandering one! A throne on high might be expected; but never one the path to which led through death and Sheol! Yes—to the proud, to the mighty, to the secure and rich, He does indeed seem the very Lord of Misrule: for He turns everything topsy-turvy in telling those who would be first that they should become last, those who would keep their lives that they should lay them down.

Today might, after all, only ever have been meant simply as a day for silly pranks and practical jokes. But even falling victim to a prank has, ultimately, a spiritual value… provided we approach it the right way. It is good to be humbled, to be surprised and shocked, to be taken off-guard by the totally unexpected. These are experiences that prepare us for the feelings that surround every true encounter with the living God; these are the feelings which are the only right ones to have when discovering an empty tomb after the crown of thorns and the cross. We can never become too comfortable, too familiar with that empty tomb, nor cease to be shocked and surprised by it. Just as it did for all Christ’s first disciples, we must allow that tomb to make fools of us; and what joyful fools we will then be!

I’ll close this reflection with one of my favorite poems by G. K. Chesterton, who certainly understood the paradoxical side of piety. If the beast Christ rode into the city that week could have sung its own magnificat, this might be it. Today, April Fools’ Day and Maundy Thursday both, is a very good day to make the Donkey’s song our own.

When fishes flew and forests walked

And figs grew upon thorn,

Some moment when the moon was blood

Then surely I was born.With monstrous head and sickening cry

And ears like errant wings,

The devil’s walking parody

On all four-footed things.The tattered outlaw of the earth,

Of ancient crooked will;

Starve, scourge, deride me: I am dumb,

I keep my secret still.Fools! For I also had my hour;

One far fierce hour and sweet:

There was a shout about my ears,

And palms before my feet.

Discussion about this post