Last updated on December 17th, 2020 at 11:13 am

As a fan of British television, I am also a fan of certain “British-isms” that are foreign to the ordinary American ear. For example, there’s a certain colloquialism, originally associated with the north of England, but now used more broadly, though not without affectation. It involves the ungrammatical use of the past participle of certain verbs. The most common instance is the verb “to sit.” Thus, one might hear a Britisher reminiscing about childhood saying something like, “I remember weekend mornings coming downstairs to find Mum sat there reading The Sunday Telegraph.” Grammatically, one ought to say Mum “was sitting” there; or else that one found her “sitting” there. I suppose, if you wanted to speak in a more perfective aspect and wanted to make clear that the action not only happened but also ceased in the past, one could describe how she “had sat” there or “had been sitting” there. The point, though, is that it’s ungrammatical to speak of Mum “sat” there like this. Nonetheless, I find it charming. (If I may be allowed a geeky aside: the way this usage seems to function is by oddly blending subject and object, or the active and passive voice. It sort of tricks the mind into imagining a fuller context of the verb: mum “had sat herself” there—or, more fancifully, she “had been sat” there by some other agency or power—fate, habit, or the household gods, I suppose. In any case, this seems akin to the Irish-ism of using “himself” or “herself” in subject or nominal predicate positions: “Himself isn’t home at the moment.” It would be a fascinating linguistic study to find whether there’s any association between these sorts of usages, or to what cultural or socio-economic forces they may relate.)

Forgive me my tangent, though. What I intended to write about is the fact that, while I do enjoy many of these quirky Britishisms, there’s one that positively rubs me the wrong way: a usage which thankfully never gained much traction here in the States (though it did enjoy a certain vogue for a time among certain people), but is very common in England. That’s the use of the word “partner” in place of “spouse” or “husband/wife.”

Now, I’m not entirely sure of the origin of this silliness in England. I can recall that here in the US, at least, when briefly this did have some currency it seemed tied up with political correctness. Although the word “non-heteronormative” (a pox upon it) was thankfully unheard of back then, looking back now we could fairly say that in today’s terms the use of “partner” in place of “spouse” seemed to have once come into fashion in order to eschew “heteronormativity.” As I said, I’m not certain of whether the origin of the usage in British English was for similar reasons… but I think it likely enough.

This word “partner” popped up several times in things I’ve been watching recently, and each time grated my nerves like a wrong note in a familiar song, and so I finally decided to try to analyse (see what I did there?) why it bothers me so much. That reflection proved more fruitful than expected. Indeed, I don’t think it is too bold to say that, in a sense, the whole history of the changing mores and values around marriage over the past three or so decades could be written around this one term. I’ll explain what I mean.

For one thing, there is a sense in which the term “partner” used this way seems odd or even anachronistic now. Granted, “spouse one and two” or “partner one and two” are still sometimes sought after in certain official applications as politically correct or “sensitive” alternatives to the old “husband and wife.” But there’s also a feeling that we’re well past such quaintness. Nowadays, many gay couples seem perfectly content to refer to themselves as “husband and husband,” “wife and wife,” or even as “husband and wife” in a gender-bending sort of way. Indeed, they might find “partner” as somewhat offensive in its attempt to be inoffensive, a relic from and reminder of a time when the public wasn’t ready to hear a lesbian speak of her “wife” or a gay man his “husband.” It’s arguable whether as much of the public are ready to hear this now as the LGBT activists seem to think, but the movement has certainly abandoned such timidity on the whole: that sort of sensibility seems oh, so utterly ’90s. Even I, when I hear someone speak of his or her “partner” today, am struck in the manner that I am when I hear someone rather over-pronouncing words like “empanada” or “burrito” when ordering Chipotle. It seems more than a bit too precious. In this fact, of the sudden seeming outdatedness of such usage, we catch a glimpse of how complete and total has been the conquest by the LGBT movement in the areas of ideas, language, and values, and how thorough the normalization of same-sex ‘marriage.’ The Overton window hasn’t so much shifted as it has been shattered, and the wall that housed it blown out, in favor of the much more modern “open concept.” So open have we become conceptually that, in a very short period of time, far from being jarred by hearing a woman speak of having a wife, we are now expected to hear with placidity a woman refer to herself as a husband!

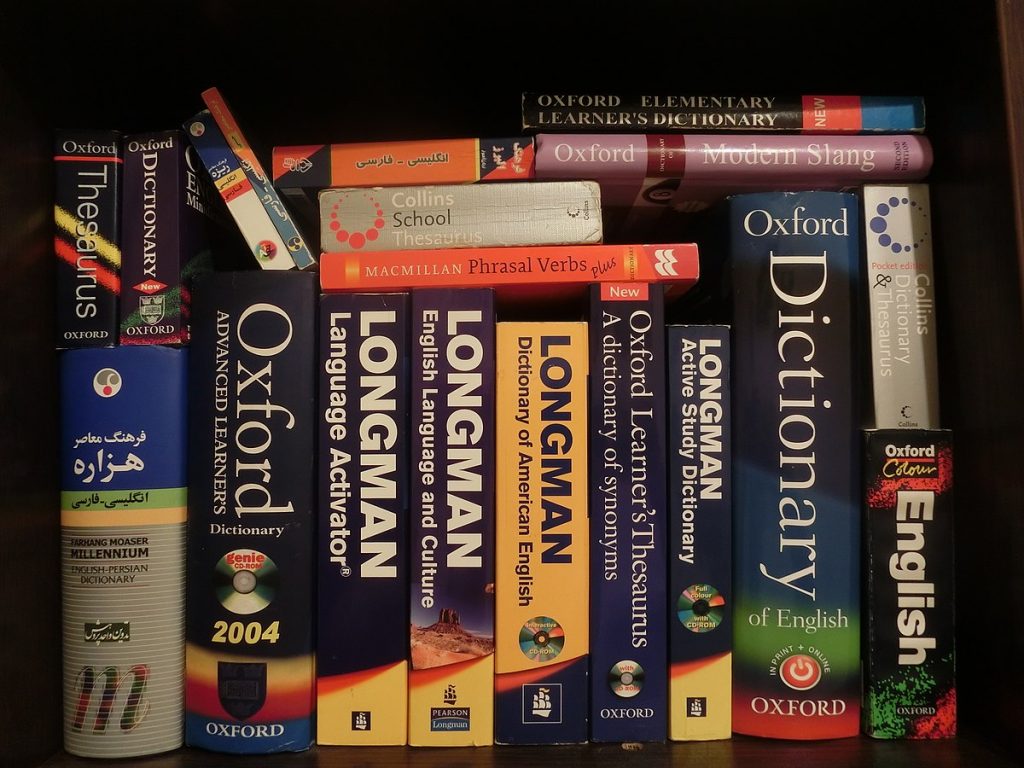

Secondly, this shift in language shows the real nature of the change from marriage as the union of a man and a woman to a union of any two persons regardless of sex. Time and again, in the push leading up to the decision in the Obergefell case to expand marriage to include same-sex couples, we were told that this wasn’t a change in the definition of the institution. This was an impossible bluff, however, as the cards were already face up on the table in the usage of the term “partner.” If you look in a dictionary for the definition of partner, you’ll find persons in romantic relationships included as one meaning of the word. But this is a relatively recent usage, and this can be seen by comparison with the definition of partnership. Here, the primary meanings relate to business and contractual relationships, e.g., “a legal relation existing between two or more persons contractually associated as joint principals in a business.” Quelle romantique! Indeed, the great irony is that it’s generally frowned upon for persons in a partnership, classically defined, to begin sleeping with one another—but suddenly people who shared a bed and a home, and maybe even offspring, started upon a time referring to one another as each one’s “partner.” Marriage, though, is not a partnership. It isn’t even, except in a secondary sense, a contract. It is a covenant. The contractual element only enters in with broader society and its interest in legally codifying, promoting, and defending the status of marriage. It wasn’t until very recently that married persons began conceiving of themselves as mere parties to a contract, like somebody leasing a Prius.

In their 2012 book, What is Marriage? Man and Woman: A Defense, scholars Sherif Girgis, Ryan T. Anderson, and Robert P. George define marriage this way: “Marriage is, of its essence, a comprehensive union: a union of will (by consent) and body (by sexual union); inherently ordered to procreation and thus the broad sharing of family life; and calling for permanent and exclusive commitment…” Does “partner” seem a congruous term to this description? Or might we suppose that part of the move toward the “partner” terminology was bound up precisely with rejecting one or more of the facets of this definition? Partnerships can be broken as easily as made, can be fleeting and—something all of the Supreme Court Justices dissenting from Obergefell pointed out—needn’t inherently be dimeric or two-partied. There is nothing intrinsic to “partnership” that demands monogamy, exclusivity, and life-long permanence. The shift from the idea of “spouse” to “partner,” then, seems a necessary cause, if not indeed sufficient, for why we are now hearing rumblings of expanding marriage even further, to include groupings of more than two persons—“throuples,” or even whole group marriages.

Finally, a last point we may take away from this reflection on the term “partner” in place of more traditional terms is the most obvious point—which, therefore, must take the anchor position of emphasis at the end. That point is this: ideas have consequences and words have meanings. Not only do words have meanings, but changing words can have the result of changing meanings and values: and one wonders if this wasn’t the long-game all along, behind this playing with the words to describe wedded couples. When the term “partner” used in this way first began to crop up in popular culture, perhaps we thought it of little import, not something to get too worked up about, just another quirk of language like misuse of the past participle “sat.” But as we sat and watched, that subtle revision in language became part of the mechanism by which our culture changed around us. It is a cautionary tale, and a lesson we’d do well to learn, as ever-more neologisms pop up around us daily: terms like “dead-naming,” “cis,” and the nonsense pronouns, “zie, zir, and zirself.” These rare and marginal usages might become the norm of thought in the future, if we’re not careful.

I close with an observation by my favorite writer, G. K. Chesterton, that I think not only captures the power of language to change thinking, but also the audacity of how progressive movements will manipulate language. He wrote: “The modern man, regarding himself as a second Adam, has undertaken to give all the creatures new names; and when we discover that he is silly about the names, the thought will cross our minds that he may be silly about the creatures. And never before, I should imagine, in the intellectual history of the world have words been used with so idiotic an indifference to their actual meaning. A word has no loyalty; it can be betrayed into any service or twisted to any treason.” He, at least, knew what words could do.