Anchored in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Pointing the Way for CSW65

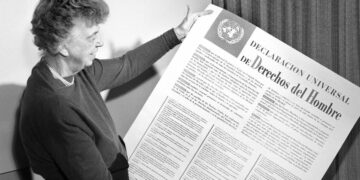

In the Secretary-General’s report1 offering recommendations to the 65th session of the Commission on the Status of Women, the first document listed in which he “anchors the theme” is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Its creation involved one of history’s most inspiring examples of what this year’s theme calls “women’s full and effective participation and decision-making in public life”: the pivotal role of Eleanor Roosevelt and her genius in leading the creation of what has been called “the gold standard” for “the moral imagination” of the world.2

The Person of Mrs. Roosevelt

When the recently widowed Mrs. Roosevelt was asked by President Truman to serve on the US delegation to the opening session in London of the newly organized United Nations, she replied, “Oh, no! It would be impossible! How could I be a delegate to help organize the United Nations when I have no background or experience in international meetings?”3

The President persisted, Eleanor relented, and so effective was her service that the United Nations soon invited her to go to Geneva to help organize the Human Rights Commission, which unanimously elected her as chairperson. Its daunting task was to establish “something never before undertaken by the nations of the world: a declaration of standards by which essential and pre-existing rights of individuals could be agreed upon as universal.”4

Throughout the next two years of seemingly endless meetings, negotiations, and amendments, Eleanor guided the creation of the Declaration and then offered a vision of the future at its adoption in December 1948. “We stand today at the threshold of a great event, both in the life of the United Nations and in the life of mankind…. This declaration may well become the international Magna Carta of all men everywhere.”5

Her words have proven prophetic. As “the first document of an ethical sort that organized humanity has ever adopted,”6 the Declaration has become “a moral guiding star”7 and “set the standard for international discussion and action on human rights.”8 In fact, “the most impressive advances in human rights,” notes Professor Mary Ann Glendon, “owe more to the moral beacon of the Declaration than to the many covenants and treaties that are now in force.”9

That the Declaration became a reality at all owes much to Eleanor’s “boundless energy and infectious enthusiasm.”10 Years later when Charles Malik, one of the chief drafters, reflected on the process that produced it, he observed, “The United States, besides championing the traditional American values, especially in respect of the supreme worth of the individual, contributed, in the person of Mrs. Roosevelt, dignity, authority and prestige.”11

Feminine Genius and the Family

Eleanor’s story has been called that “of a determined woman who willed herself to become a voice for the voiceless, a fighter for freedom, and a tribune for the nobility of America’s true values.”12 Her remarkable leadership role in producing the Declaration illustrates the “feminine genius” to which Pope John Paul II referred in 1995 on the eve of the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing.13 Two decades later when Archbishop Bernardito Auza addressed the UN Commission on the Status of Women in New York, he offered an invitation whose relevance increases with time: “John Paul II referred to this special brilliance of women in caring for the intrinsic dignity of everyone and for nurturing others’ gifts as the ‘feminine genius.’ Today we are here to ponder that feminine genius, to celebrate it, to thank God for it, and to thank and praise women for it.”14

Pondering that feminine genius today, the example of Eleanor Roosevelt demonstrates not only the power that can be unleashed by women’s full and effective participation and decision-making in public life, but also the synergy that can arise from such participation. Eleanor was, according to Professor Glendon, one of “four in particular [who] played crucial roles” in drafting the Declaration.15 And “though they differed on many points, [they] were as one in their belief in the priority of culture” and “the ‘small places’ where people first learn about their rights and how to exercise them responsibly.” As Eleanor expressed, “Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home—so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world.”16

René Cassin of France similarly understood that “the human being was above all a social being,” and while “freedom of individual conscience was inviolable,” yet “individual rights were embodied in groups, without which they could not exist.”17 The Confucian tradition of China’s Peng-chun Chang recognized “the individual as a vitally integrated element within a larger familial, social, political, and cosmic whole” in which “goodness is something that can be manifested only in relation to other persons, in a community of fellow human beings.”18 And Lebanese delegate Charles Malik knew that of all the social groups, only “the family deriving from marriage is the natural and fundamental group unit of society” and “is endowed by the Creator with inalienable rights,” making it “the cradle of all human rights and liberties.”19

From such combined genius came article 16(3), which stands out for its acknowledgment of “the only right in the Declaration that specifically devolves to a group rather than an individual,”20 a group recognized as the foundation of civilization itself: “The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.” Elaborating on the “natural family,” Pope Francis referred to the “complementarity between man and woman” which “lies at the foundation of marriage and the family” and creates the optimum environment “for the child’s growth and emotional development,” resulting in “a unique, natural, fundamental and beautiful good for people, families, communities and societies.”21

In the words of Michael Novak, “the roles of a father and a mother, and of children with respect to them, is the absolutely critical center of social force.”22 Even so, one parental role stands out as indispensable. “Mothers play a critical role in the family,” stated Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon. “The mother-child relationship is vital for the healthy development of children…. We face multiple challenges in our changing world, but one factor remains constant: the timeless importance of mothers and their invaluable contribution to raising the next generation.”23

As the important work of CSW65 proceeds, we urge that it truly be anchored in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by honoring women’s unique feminine genius, including and especially her vital role in society’s natural and fundamental group unit, the family.

International Organization for the Family

Center for Family and Human Rights

United Families International

CitizenGo, Spain

Latin American Alliance for the Family

Universal Peace Federation

Family Policy Institute, South Africa

Novae Terrae Foundation, Italy

Real Women of Canada

Provive, Venezuela

Institute for Family Policy, Spain

FamilyPolicy.RU Advocacy Group, Russia

1. Report of the Secretary-General, 21 December 2020, “Women’s full and effective participation and decision-making in public life, as well as the elimination of violence, for achieving gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls.” https://undocs.org/E/CN.6/2021/3.

2. Seamus Heaney, “Human Rights, Poetic Redress,” Irish Times, March 15, 2008, https://irishtimes.com/news/human-rights-poetic-redress-1.903757.

3. Elliott Roosevelt and James Brough, Mother R: Eleanor Roosevelt’s Untold Story (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1977), 68-69.

4. David Michaelis, Eleanor (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020), 457.

5. Statement to the United Nations General Assembly on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, December 9, 1948, available at https://erpapers.columbian.gwu.edu/statement-united-nations-general-assembly-universal-declaration-human-rights-1948.

6. René Cassin, Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1968, https://nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1968/cassin/lecture.

7. Hans Ingvar Roth, P. C. Chang and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 135.

8. Lynn Hunt, Inventing Human Rights: A History (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2007), 205.

9. Mary Ann Glendon, A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (New York: Random House, 2001), 236.

10. Johannes Morsink, The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Origins, Drafting, and Intent (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), 32. Eleanor herself would later reflect, “I had really only three assets: I was keenly interested, I accepted every challenge and opportunity to learn more, and I had great energy and self-discipline.” Roosevelt and Brough, 105.

11. Habib C. Malik, ed., The Challenge of Human Rights: Charles Malik and the Universal Declaration (Oxford: Charles Malik Foundation: Centre for Lebanese Studies, 2000), 156.

12. Cover endorsement by Walter Isaacson of Michaelis, Eleanor.

13. “Letter of Pope John Paul II to Women,” https://vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/letters/1995/documents/hf_jp-ii_let_29061995_women.html.

14. H.E. Archbishop Bernardito Auza, “Women Promoting Human Dignity,” https://holyseemission.org/contents//statements/55e34d37d39447.15475237.php.

15. “Among the Declaration’s framers, four in particular played crucial roles: Peng-chun Chang, the Chinese philosopher, diplomat, and playwright who was adept at translating across cultural divides; Nobel Peace Prize laureate René Cassin, the legal genius of the Free French, who transformed what might have been a mere list or ‘bill’ of rights into a geodesic dome of interlocking principles; Charles Malik, existentialist philosopher turned master diplomat, a student of Alfred North Whitehead and Martin Heidegger, who steered the Declaration to adoption by the UN General Assembly in the tense cold war atmosphere of 1948; and Eleanor Roosevelt, whose prestige and personal qualities enabled her to influence key decisions of the country that had emerged from the war as the most powerful nation in the world. Chang, Cassin, Malik, and Roosevelt were the right people at the right time. But for the unique gifts of each of these four, the Declaration might never have seen the light of day.” Glendon, xx-xxi.

16. Glendon, 239-240.

17. Jay Winter and Antoine Prost, René Cassin and Human Rights: From the Great War to the Universal Declaration (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 244.

18. Daniel K. Gardner, The Four Books: The Basic Teachings of the Later Confucian Tradition (Indianapolis, Indiana: Hacket Publishing Company, 2007), 139.

19. Morsink, 254.

20. Glenn Mitoma, “Charles H. Malik and Human Rights: Notes on a Biography,” Biography 33.1 (Winter 2010), 226.

21. “Address of His Holiness Pope Francis to Participants in the International Colloquium on the Complementarity Between Man and Woman,” 17 November 2014, https://vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2014/november/documents/papa-francesco_20141117_congregazione-dottrina-fede.html.

22. Michael Novak, “The Family out of Favor,” Harper’s Magazine 252, no. 1511 (1 April 1976): 38.

23. “‘Timeless Importance of Mothers’ One Constant in Changing World Facing Multiple Challenges, Says Secretary-General in Message on Day of Families,” 6 May 2009, https://un.org/press/en/2009/sgsm12227.doc.htm.

Discussion about this post