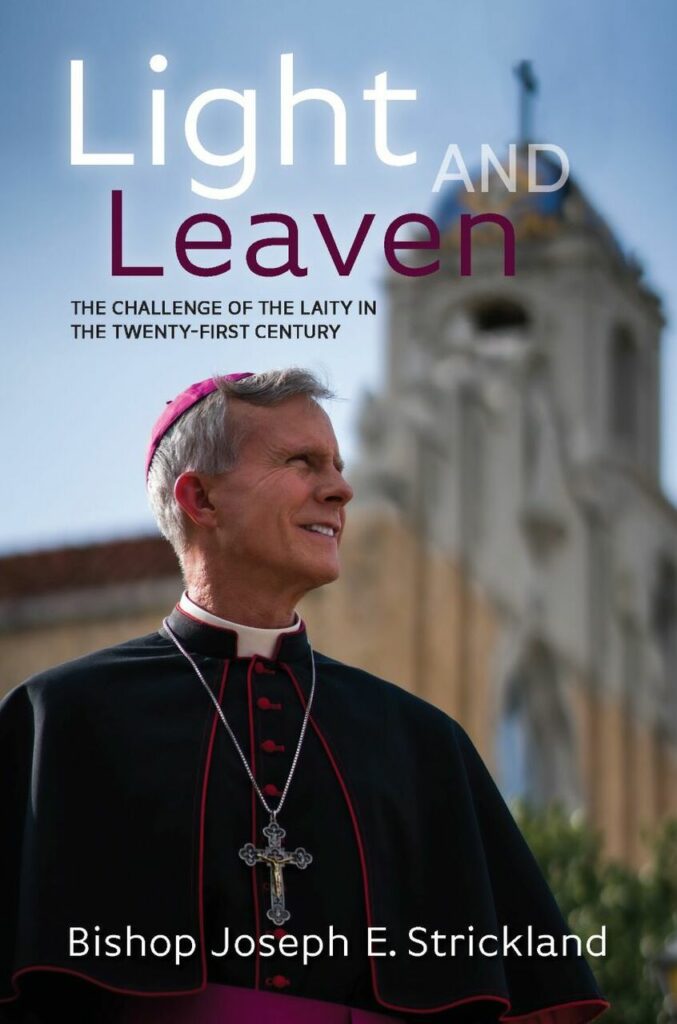

Though his diocese is in tiny Tyler, Texas, Bishop John J. Strickland has outsized influence among American Catholic bishops due to his rock-solid defense of traditional Church teaching and morality. They say “Don’t mess with Texas,” and now they can say “Don’t mess with Bishop Strickland of Texas” if you are a left-wing prelate or layman. In his 2021 book Light and Leaven—The Challenge of the Laity in the Twenty-First Century, Bishop Strickland attacks the moral relativism plaguing our culture and proposes living in the truth of the Gospel—and being a sign of contradiction—as the best way to overcome it.

Bishop Strickland opens up his book by noting that Christians are living in truly dark moral times. “The world is not just post-Christian; it’s post-God,” he writes. “There’s an angry resistance to truth and authority. If there is no God, then there is no authority, and no one can tell me what to do. That’s how we operate now. Moral anarchy.” (26) And this moral anarchy is leading many people to despair: “And when God is gone, human beings are just little, individual, formless wastelands with no image, all on our own in a meaningless moral void. It’s such an ugly, bankrupt view of life… If you’re on that track, it’s hard to find meaning, much less hope, in your life.” (29) Indeed, we could be forgiven for thinking we are living in the days of the decadent Roman Empire, where “the Caesars thought they were gods. There was abortion and infanticide. There was awful sexual debauchery. Look at the brokenness of the Roman Empire and fast forward twenty-centuries to where we are now, and it’s the same brokenness….” (31)

But what is the reason for this brokenness? It is the same reason why Adam and Eve lost paradise: by believing the falsehood that “Ye shall be as gods.” It is because of moral relativism and its belief that we are the creators of our “own” truth. Strickland writes: “There has always been sin, of course. But in our age, we seem to think we’re God. We think we’re in charge, that we’re in control, and that is the root issue.” (30-31) As a result of this moral relativism, people tend to denigrate anything that could shackle their whims and impose anything on them, from religion and biology to the family. He states:

Religion, God’s agency, is viewed not as liberating and enlightening but oppressive and controlling…The idea that human beings are made [or created] male and female is oppressive because it doesn’t let people make humanity whatever they want it to be. Marriage as a natural institution ordered to one man and one woman for life oppresses people’s wish to form sexual partnerships with whatever person or persons they choose—or end them at will. It’s oppressive not to let people kill babies in the womb because we all should be allowed to define human life for ourselves. (27)

While the times are indeed dark, Strickland urges Christians to engage the culture, rather that take the “Benedict Option” of retreating from the world to live in insular Christian communities. Christians “need to be leaven for the world—not put up fortress walls and take cover in their beautiful domestic church; that is the opposite of what Jesus said.” (122) So how should we engage the culture?

We can best engage the culture, Strickland argues, by living in the truth of the Gospel. “What is the most basic answer to this crisis? Live your faith. Seek sanctity.” (111) We must thoroughly examine ourselves to ensure we are living according to the standards of Christ—and then ask for God’s grace to live according to those standards. “Just be as faithful as you can and trust in the Lord,” he writes. “Never despair, never give up, never believe that it’s too late or you can’t do anything good.” (113-14)

But living according to the truth, the Gospel, will not always be easy. “To live the truth fully takes courage and often comes with sacrifice—not always in money or material goods but sometimes in our families, or in our ambitions, or in our freedoms. Yet the rewards are joy and peace.” (117) Indeed, living in the truth will bring us into conflict with the world as we will be signs of contradiction:

Sometimes you will be accused of being a “divider” if you refuse to go along with the majority when the majority is wrong, whatever the issue. But this is the kind of division—to be a sign of contraction to the world—that shows you’re seeking to live the truth of the gospel… So the idea that we should keep our mouths shut instead of “dividing,” or the related idea that mercy comes before truth, is an insidious falsehood that is totally off the mark. (118-19)

So what are some ways we can live in the truth and be “signs of contradiction?” First and foremost, we can live according to the Church’s teaching on sexuality in order to combat the disastrous fallout of the sexual revolution whose foundation is moral relativism. Strickland writes: “ The sexual revolution has done very serious damage to humanity. I think people are going to say, as we look back on this sexual revolution from a more distant future, that it really messed up humanity.” (128) One of the best ways we can do this is by restoring the sanctity of marriage. Bishop Strickland states: “To repair the damage, we must start with helping people be formed to really live what marriage is, because marriage is the only place where sexual life is lived in a healthy way.” (128) What happens when you don’t respect the institution of marriage can be seen all around us today: “When you don’t have a man and woman, one man and one woman committed for life in marriage, loving each other and open to bearing and raising children, things go haywire. All you have to do is look out your window and see how things are haywire with broken marriages, with single parents, with kids who are lost and not being directed,” he writes. (131) For people struggling with issues regarding sexuality, whether related to having sex outside of marriage, having same sex attraction, or having gender confusion, we are not to show any signs of bigotry, Strickland states. However, “we don’t overcome bigotry or harsh judgmentalism by saying that immoral acts are perfectly fine; to me, that’s not mercy but a deeper bigotry. It’s denying the truth to people who desperately need it.” (134-35)

A second way to be a sign of contradiction is to be solidly in favor of a culture of life. “Abortion is not just the preeminent political issue of the moment in our country; it is the preeminent issue of our time in the whole world… Abortion is the murder of the most vulnerable, the weakest, the tiniest of those on the spectrum of human life—how can it not be preeminent?” (142-42) Significantly, Strickland argues that abortion must always be front and center and can never be considered just one issue among many, as advocated by liberal Catholics who support the “seamless garment” position. And in fighting for life, we must make sure to support everyone involved—the child, the mother, and the father. Christian crisis pregnancy centers located all across the nation have gone a long way toward this end but more can still be done.

In his book Light and Leaven, Bishop John Strickland lays a lethal blow to moral relativism and proposes living according to the truth of the Gospel as the best way to overcome it. “The more the world moves into the darkness of relativism, where everyone’s a God and everyone can decide what’s true, the more Satan’s hatred for us meets its purpose,” he writes. (149) That is why living according to the truth is so vital. But doing this will not be easy; what is needed, he says, is moral courage: “Can we find the courage to stand up and say, for instance, that marriage is between one man and one woman for life, open to children? That isn’t an opinion. That isn’t a belief. That is what God’s plan for human beings is. That is marriage. That is reality. When we decide we have a different opinion form reality, we get messed up, and that is where we are.” (172) May God grant us such courage.