After years spent unsuccessfully trying to inject human stem cells into sheep and pig embryos, scientists have now ventured into uncharted territory by successfully mixing human and monkey cells.

In the medical journal Cell, the international team of scientists at the fore of this groundbreaking development describes the procedure as an attempt to find new ways to produce organs for people who need transplants. But some scientists remain concerned as to what kind of ground is being broken.

Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, co-author of the study and professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Sciences in La Jolla, California, is very excited about the breakthrough and how it can address the demand for organ transplants which he calls “one of the major problems in medicine”.

“This knowledge will allow us to go back now and try to re-engineer these pathways that are successful for allowing appropriate development of human cells in these other animals”.

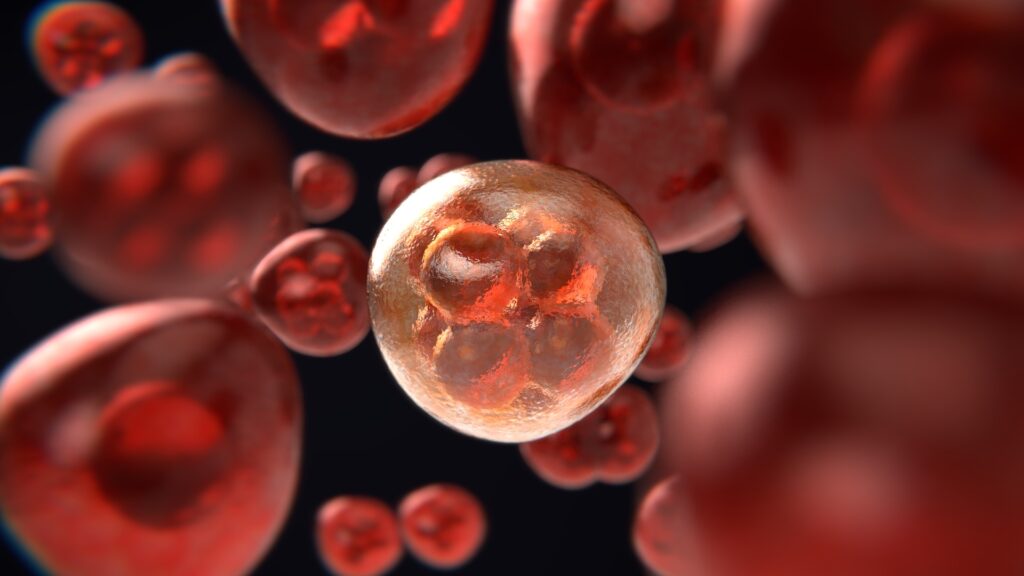

The failure of human-to-pig/sheep commingling in recent years led Belmonte to collaborate with other scientists – the majority coming from China – in order to “try something different”. The experiment involved the use of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPS); human skin or blood cells that have been “reprogrammed” for ulterior uses. The researchers injected 25 iPS cells into embryos from macaque monkeys, which have a closer genetic makeup to humans than pigs or sheep. A day later, human cells were detected in 132 of the embryos. In a 19-day span of studying the embryos, the scientists documented findings on human/animal cellular communication which they hope will lead to new ways to “grow organs for transplantation”.

Science uses the term “chimera”, to describe a single organism composed of cells with more than one distinct genotype. In Greek mythology, a chimera is a fire-breathing she-monster having a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and a serpent’s tail.

With lines blurring between fiction and reality, more than a few from within the scientific community are more than a little wary of this new study. Said Kirstin Matthews, a fellow for science and technology at Rice University’s Baker Institute, “My first question is: Why? I think the public is going to be concerned, and I am as well, that we’re just kind of pushing forward with science without having a proper conversation about what we should or should not do.”

Belmonte says that the team’s goal was “not to generate any new organism, any monster. We are trying to understand how cells from different organisms communicate with one another.”

But some biological ethicists are concerned that some scientist could push this envelope into the creation of a baby made out of such an embryo. Or that it could produce animals that have human sperm or eggs.

Said Stanford University bioethicist Hank Greely, “I think rogue scientists are few and far between. But they’re not zero. So I do think it’s an appropriate time for us to start thinking about, ‘Should we ever let these go beyond a petri dish?’ ”

Matthews poses some other questions. “Should it be regulated as human because it has a significant proportion of human cells in it? Or should it be regulated just as an animal? Or something else? At what point are you taking something and using it for organs when it actually is starting to think and have logic?”