Last updated on March 23rd, 2021 at 04:25 pm

[This is the first installment in a five-part essay exploring the history of the concept of “gender” in its origins and stages of development. Part two was published simultaneously, part three can be found here, and the later two sections are to follow.—Ed.]

“Coded hate speech”?

Recently, during an exchange about the Equality Act, I was told that I’d used a term that is a “coded” form of hate speech, a term which functions as a “dog whistle” for “transphobia,” and which has its origins in “internet conspiracy theories.”

The term? “Gender theory.”

In another recent discussion, this time with a friend seeking advice on how to discuss “transgenderism” with certain unsympathetic family members, I gently suggested at one point during his rehearsal that he say rather “sex” or, if he preferred, “biological sex,” when speaking about the matter.

I also wrote recently, admittedly a bit reluctantly, on Marjorie Taylor Greene’s protest in the House office building consisting of a sign that read, “There are TWO genders: Male and Female.” In that context, given the purpose of my piece and the purpose and circumstances of Greene’s protest, I prescinded from noting that her sign was, to me, not quite correct—which I will explain below.

These three occurrences suggested to me that I should find occasion to provide a bit of primer on the subject of “sex and gender,” and the language and history at play in the discourse surrounding these topics.

“Gender” is a construct… of language

“Gender,” used as a term to refer to human persons, is a relatively novel coinage. It arises in the 20th century, as part of certain new conceptions of social psychology, and the usage was subsequently picked up by feminist scholars and others who found it useful for their own purposes.

When speaking of human beings, the term “sex” formerly had been normative. “Gender,” on the other hand, was a concept related (as it were) in a metaphorical way, but quite distinct: it primarily had to do with language.

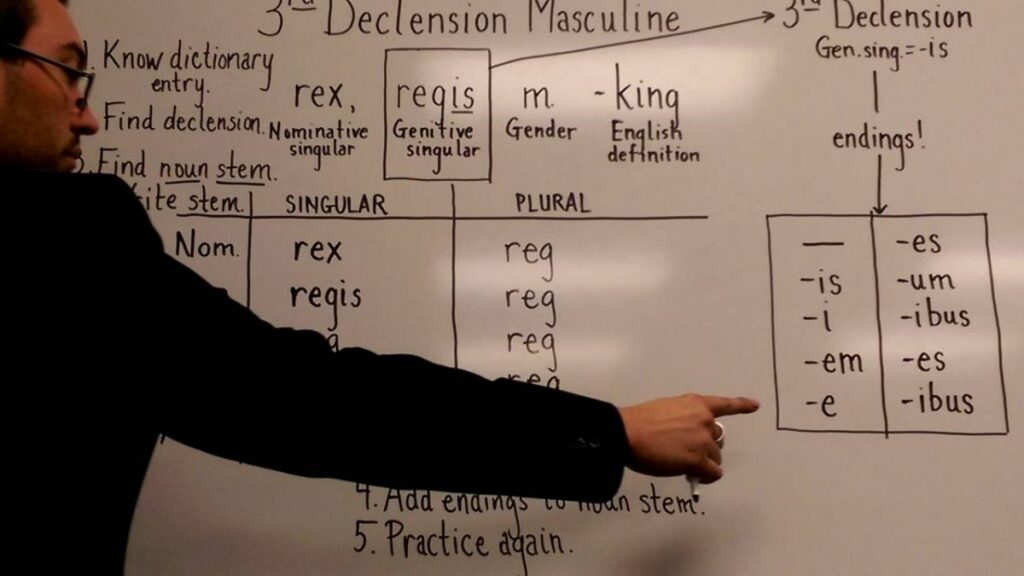

See, in most languages, words have a “gender”—e.g., masculine or feminine or neuter. (This is what I meant above by reference to Greene’s sign being “not quite correct”: there can be a third or more “genders” in a language.) Some modern languages still have three genders, like German; whereas some, like French and Spanish, have reduced it down to just masculine and feminine; and still some others, like English, have essentially lost grammatical gender for all words except pronouns. (A friend with whom I was discussing this asked, “What about words like ‘actress’ and ‘actor’?” The fact is what we see happening in these words is more dis-analogous than analogous to what we mean by grammatical gender. In a language with gendered nouns, it’d be more likely that you’d have a single word, “actor,” which might be a feminine noun, regardless of whether it referred to a male or female actor. Or, to look at it another way, suppose describing an actress and saying she was wearing red shoes, a red dress, and had red hair. In a gendered grammar, you might have three different spellings of the same adjective “red,” because in that language “shoes” might be feminine, “dress” neuter, and “hair” masculine. That’s more of what we mean when we speak of “gendered nouns.”)

Furthermore, note how while linguistic gender and referential sex have aligned sometimes, there are also notable exceptions that prove the rule that it isn’t about sex. For instance, “girl” in German (Mädchen) is grammatically neuter. First-year Latin students, on the other hand, will be familiar with how the word for “farmer” in Latin (agricola, -ae) is morphologically feminine (a word of the first declension), but is treated as masculine for agreement with modifiers adjectives. A more advanced Latin student might know that the word “uterus” is a Latin loan-word (where it also referred to the womb), and yet it is a “masculine” noun! This, of course, would seem very odd if the “sexual” underpinnings of grammatical gender were pressed too far. Grammatical gender simply doesn’t work this way. Thus, certain animals’ names are masculine or feminine grammatically according to species, regardless of whether one is speaking of a particular animal that is male or female. And words that don’t seem to have any implicit sexual connotations or even relational roles—words like “sky” and “sea” and “rock”—all have their assigned “genders.”

A rocky discussion

An example based on that last word, “rock,” might be illuminative. Anyone who has ever done or encountered New Testament biblical apologetics might be familiar with the debate over whether Simon bar Jonah is “the Rock” (in Matthew 16:18), since the new name Christ gives to Simon is rendered in the Greek as masculine—πέτρος—even though the play on words relates this to the feminine noun “rock”—πέτρα. I am not interested here in commenting on this interesting discussion or the relative merits of any arguments thereunto pertaining. My point here is to notice why the confusion arises: it has to do precisely with this distinction we are making. While both words have a gender, only the man Peter additionally has a sex, which the rock does not (with apologies to Duane Johnson). “Rock” in Greek is a feminine noun, but Matthew renders it in a masculine form when referring to Peter because to do otherwise might confuse the reader.

From this we can see that it is only accurate, and not at all “coded hate speech,” to speak of a “theory of gender” or of “theories of gender” that arose and flourished in the second half of the 20th century. It is simply an undisputed fact that, to anyone before this time, “gender” meant a quality having to do with grammatical forms of words.

If one asked an early 20th century English speaker “how many genders are there?” the answer would likely have been “three.” This is because that speaker likely would have had “a little Latin and less Greek” from grammar school, and assumed you meant Latin since English isn’t really a gendered language; but the speaker would have known in any case you were asking a question about language and not about human beings.

Now, however, the term “gender” has become a rocky subject, with much different meaning than it had historically. How did this happen? Well, in our next part, we will examine how the first tectonic shift in the meaning of this word happened. It began in 1950s…

[Continue reading in part two.]