[This article originally appeared in SALVO (www.salvomag.com) on September 30, 2020; it is reproduced here with permission. – Ed.]

When one reflects upon the current American political climate—and “reflecting” isn’t even really necessary, because that climate is being stuffed down the collective American throat right now—it is easy to become disillusioned, depressed, perhaps even readier than ever to move to, say, Costa Rica.

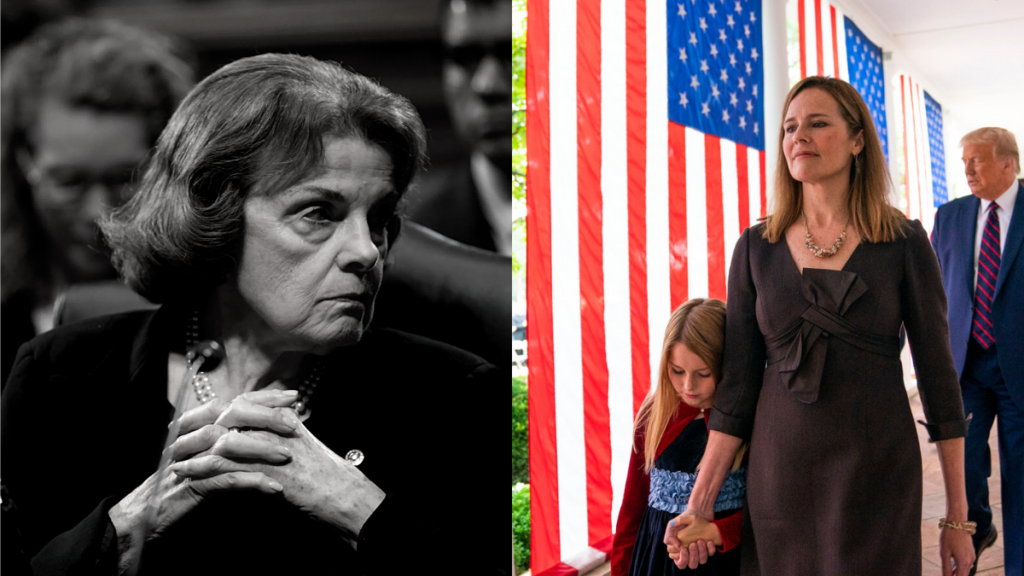

In such reflections, Amy Coney Barrett is a welcome breath of fresh air. She has more class, brilliance, presence, and poise than either of our current presidential candidates, as was made painfully obvious in Tuesday’s debate. But she is something else, too. As a POLITICO story puts it, she is “a new feminist icon.”

If this seems counterintuitive, it’s because generations of American women have been told that to get ahead in life, you have to follow the life script of a man. In other words, sacrifice the very things that make you “feminine”—specifically, the biologically unique female ability to conceive, bear, and nurse children. But if first-wave feminism was about getting women the right to vote, and second wave feminism was about getting them cultural and workplace equality, third-wave feminism is about changing the culture itself and the place of family in the workplace.

As the POLITICO story noted, Senator Dianne Feinstein told Barrett at the latter’s senate confirmation hearing in 2017, “You are controversial because many of us that have lived lives as women really recognize the value of finally being able to control our reproductive systems, and Roe entered into that, obviously.” This is the second-wave feminist script. Women can “live lives as women” only by gaining “control” over reproduction. But for Feinstein, “control” means contraception and abortion. This is the sentiment expressed by Michelle Williams in her Golden Globe acceptance speech earlier this year. “Things happen” to women’s and girls’ bodies that they did not choose. Williams closed, “I would not have been able to do this without employing a woman’s right to choose.” In this view—the view held by Williams, and Feinstein, and Ginsburg, and countless others—women’s very bodies, their reproduction, and their reproductive timeline, are inimical to their life’s dreams.

For Barrett, on the other hand, “control” over career and motherhood seems to mean something far, far different. In 2019, Barrett was asked how she had managed to achieve so much, while also being the mother of seven children. Her response is that both she and her husband, Jesse (also an attorney), have taken turns at “the heavy lifting” of parenting. Right now, she says, he is definitely doing more of it, but there have been times when she was the heavy lifter. “We’ve gone in cycles,” Barrett said. “We evaluated at every step whether things were working well for the family, for the job I was in . . . but it was always working and it worked well: the kids were very happy, I loved teaching.” She continued to say that for both her and her husband, the children came first, their careers, second. But they didn’t need to sacrifice either—and an aunt of her husband’s helped immensely with childcare.

What Barrett’s marriage exemplifies is the idea of sexual complementarity in the caring of children. Author Wendell Berry wrote in The Unsettling of America that only with the advent of the Industrial Revolution did we, for the first time, see the sexual division of labor—wherein caretaking became a primarily female responsibility. Before that, both sexes partook equally in maintaining the family occupation (farming, an artisan’s shop, etc.), while also caring for the children and household. Barrett and her husband get this. They have put their family first—and found that when they cooperated, when caretaking was the joint responsibility of both spouses, and when they communicated, both they and their children thrived. As POLITICO put it, “When greater numbers of us understand the cultural priority of caregiving, a movement will grow strong enough to challenge the dominant market mentality that disfavors family obligation for both women and men.” Men do not want to spend all their time away from their family, either. Our workplaces need to reflect these deep and universal human desires.

For now, though, we can appreciate that a mother of seven children, a brilliant mind and a seemingly gracious, accomplished, and well-liked person, is a nominee for the nation’s highest court. (Notably, of the four women who have been on the Supreme Court so far, only one—Ruth Bader Ginsburg—was a mother.) May her example lead other women to realize that they don’t need to sacrifice their bodies or those of their children on the altar of career.